By Susan Godstone, Silver Lumsdaine, and Arezu Sarvestani

As UC San Francisco honors Black History Month this February, it is with an awareness that we are at an inflection point in history. Institutions cannot ignore the structural racism that perpetuates health inequities and undermines Black achievement, well-being, and security.

ANTI-RACISM EFFORTS

Through UCSF’s Anti-Racism Initiative, Chancellor Hawgood and senior administrators at UCSF are partnering with stakeholders across the campus and UCSF Health to address racism in health care and research as well as in the recruitment practices of faculty and management.

As we celebrated Black culture, community, and art on UCSF's social media channels, we asked some of our faculty, staff, and students about their experiences, their inspirations, and where they find hope for the future.

Leah Pimentel, Assistant Director of Community Relations

Tell us about your work.

I am the UCSF representative to Mission Bay, Dogpatch, Potrero, the Mission, Bayview, and any other area on the Eastern side of San Francisco.

My job is to be a connector and to understand communities and their needs, hesitations, reservations and barriers. I help them engage with UCSF Health services, whether they need help with things like diabetic kits, blood pressure screenings, flu shots, and so on. I work with the community as well as businesses and stakeholders, bringing everyone to the table to find opportunities for engagement.

I also served on UCSF’s Child Dependent Care Task Force (CDCT), where I helped UCSF employees, faculty, and staff get access to extra support during the pandemic. Parents and caregivers often bank their vacation and sick time in case of a crisis at home, so you’ll be ready in case of the “what if.” But COVID doesn't work like that, COVID has its own schedule. I served on the CDCT team to ensure that people had access and that they knew that someone on the other end was listening to them and was looking out for them.

What or who inspires you to work in health/science?

My mother was a nurse at Kaiser for over 40 years, and I frequently went to work with her. My job was engaging with and reading to the cancer patients. I remember one girl, her name was Becky. That was my first time being with a cancer patient that didn't survive. She was a young girl; I was around 13 and she was just a little older than I was. While she was going through her cancer treatment, I would sit with her. We would talk about all the things that we wanted to do when we got older, like shopping for prom dresses and going to the same college.

I'll always remember being there the day that she died, and how the head nurse of the department took her parents aside to talk to them. I just remember staring at that closed door, thinking about how long they were in there. That experience made me want to be in a field that contributes to changing that — to finding a cure, making an impact, even if it’s just being there to listen to you and reassure you in your time of need.

I never knew about community relations growing up, and I want to expose the next generation to these different opportunities that are on the table.

LEAH PIMENTEL, ASSISTANT DIRECTORUCSF Community & Government Relations

What kind of messages did you get about Black people in science/health as you were growing up? And what, if anything, do you think anything has changed?

I think the message that was the most impactful to me was the Henrietta Lacks story. I remember hearing about it and feeling shocked and outraged that I’d never learned about it in school. I became fascinated by how one woman’s cells brought about so much change. But it also highlighted all the things that cause hesitation in the African-American community when it comes to medicine, even to this day.

For example, I hear a lot of hesitation around the COVID vaccines. When people ask me whether they should I get it, I tell them I encouraged my dad to get his shot and I wouldn’t cause him harm. We have to recognize those hesitations, and take that initiative to eliminate barriers to entry and understand where people are coming from. I’ve worked hard to develop skills in cultural communication and a cultural understanding of historical issues, because these things are passed down from generation to generation to generation.

I think that's why we need an increase of minorities and African-Americans in the health field, so everyone can feel that connection, that someone understands where you’re coming from. It's that relatability of someone who understands you, hears you, sees you. Without that trust, you're not willing to move forward.

What excites you about the next generation of Black people in science and medicine?

Being a mom, I see how science is a part of my kid’s world every day, and I see his excitement and creativity as he envisions what he’s going to create and what he’s going to cure. I didn't have that growing up, technology wasn't where it is today. I’m excited about the ways that people are fostering creativity and mentoring the next generation, because that generation will be a product of the efforts that we're making now in trying to provide opportunities in STEM and in health. I'm looking forward to a time where you see entire departments of African-Americans, and a rainbow of diversity and inclusion. With the COVID vaccine, we’ve seen what can happen when everyone works together. I want to see what the next generation will cure.

There are so many fields within health, like my work in community relations. I never knew about community relations growing up, and I want to expose the next generation to these different opportunities that are on the table. I’ve talked to my son’s class, and they knew about being doctors and nurses, but they don't know all the other possibilities.

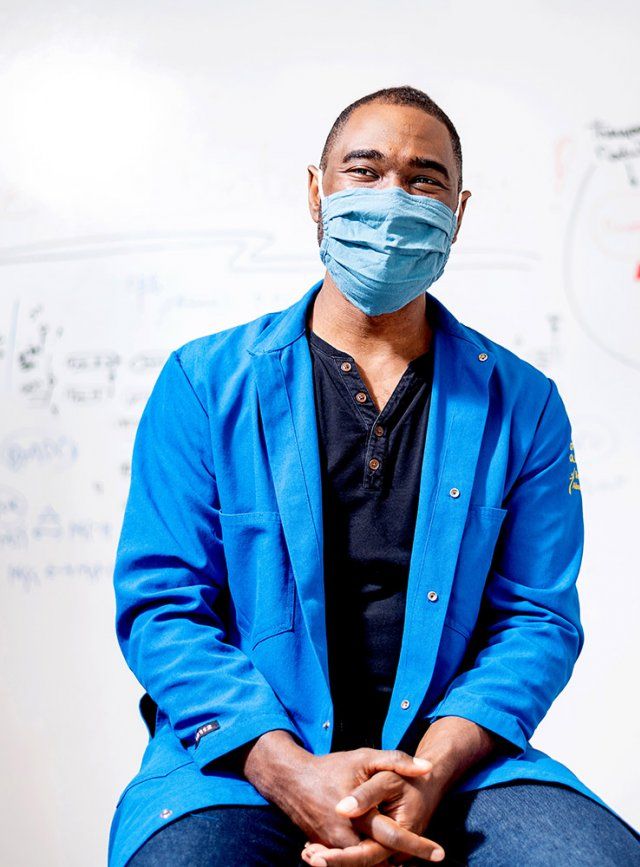

Matthew Bucknor, MD, Associate Professor in the UCSF Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging

Tell us about your work.

One of my main areas of research is a technology known as high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU). This is a completely non-invasive way of treating tumors in the body with focused sound energy to create heat, similar to the way you can use a magnifying glass to focus sunlight. I have expertise in using this technique, guided by MRI, to treat a variety of tumors in the body, and I’m working to develop new HIFU indications for treating cancer. Additionally, I feel passionately about making sure that all patients have equal access to state-of-the-art imaging and imaging technologies like HIFU, so I have several active research projects investigating health disparities related to the use of imaging. I’m interested in understanding how patient demographics affect our use of imaging and how we can work to correct these kinds of disparities in care.

What or who inspires you to do what you do?

I’m inspired by the people who came before me: my parents who came to this country with their dreams, my wonderful mentors, my incredible wife and kids, and the many generations that struggled, sacrificed, and persevered so that I would have the opportunity to help people doing what I love every day. I’m inspired by my patients—their courage in the face of disease. And I’m inspired by the opportunity to be part of a department, a university, and a medical center with a vision to be a world leader in health care and advancing health equity.

What kind of messages did you get about Black people in science/medicine as you were growing up? And what, if anything, do you think anything has changed?

My mom insisted on finding me a Black pediatrician as a child, who was the only doctor I ever really remember seeing. That consistency of seeing a Black man in medicine every single year had a big impact on me. It normalized the possibility of a career in medicine if that was something that I wanted to do.

I feel like the message around Black people in science/medicine is changing in important ways. We are seeing more positive images of Black people in science/medicine all the time, whether we’re talking about Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett leading the effort to develop one of our highly effective COVID-19 vaccines, or the leaders of many health care organizations across the country—ours included. There are more opportunities to see Black excellence on display in science/medicine than ever before. I also feel like the message that we need more Black voices in healthcare—that it makes our organizations stronger, that it allows us to provide the highest quality care possible, that we can’t allow another generation to go by in which the number of Black male medical students matriculating, for example, does not change at all in absolute numbers—this message is resonating deeply in this moment. It gives me more hope than ever going forward.

My mom insisted on finding me a Black pediatrician as a child. [...] That consistency of seeing a Black man in medicine every single year had a big impact on me.

MATTHEW BUCKNOR, MD, ASSOCIATE PROFESSORUCSF Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging

Was there an experience that really affirmed (or reaffirmed) your commitment to your field?

There wasn’t a single epiphany in choosing radiology. My experiences in medical school on every rotation—seeing how many lives were affected by imaging interpretation and image-guided procedures—moved me steadily in this direction. I was attracted to the idea of being able to help advance the care of patients in so many important and innovative ways.

I did have an epiphany around choosing academics when an attending came up to me after I gave a research presentation. She saw the excitement that I had in delivering it and reflected that back to me. I think that was important. I’ll never forget that moment.

Did you ever have a moment of doubt, in which you thought you might not continue in science/health? And how did you move through that?

No, but I have had thoughts about adding on…I’m also passionate about the medical humanities and creative writing, for example, which I see as a way to further promote wellbeing and diversity and inclusion in medicine. But I couldn’t imagine not having a career in science/health.

What excites you about the next generation of Black people in science and medicine?

I’m excited about the level of sheer brilliance, passion, and determination I see in the next generation of Black people in science/medicine, and what they might be able to achieve within institutions with a renewed commitment to promoting equity. I mean just imagine what could possibly be unleashed. There’s an opportunity here to transform science and medicine. To radically change our systems in a way that advances the best outcomes with an approach that for the first time really centers equity at the population level. It’s incredible to bear witness to this moment.

Joel Babdor, PhD, Postdoctoral Scholar in the UCSF Department of Otolaryngology

Tell us about your work.

I investigate how the microbiome -- the bacteria that live in our body -- influence the immune system in both healthy individuals and in patients that have diseases where treatment involves the immune system. Immunosuppressants have long been used to reduce the activity of the immune system to treat patients with autoimmune disorders or organ transplants. More recently, doctors have begun boosting the immune system in different contexts, including cancer, using new drugs called immunotherapies. These treatments work better in some individuals than others, and it seems like the gut microbiome may play a role. Everybody has a different microbiome and, if we can understand the underlying mechanisms, we might be able to help patients better respond to immune modulators.

I’m also the co-founder of #BlackInImmuno, with a group of researchers who, like me, wanted to create a platform for Black immunologists to share with the world about their work and their journey. We got together on social media to organize and plan #BlackInImmunoWeek, following the model of the “Black-in-X” weeks that we'd seen during the summer of 2020.

What or who inspires you to do what you do?

The first memory that I have about being excited about science is related to a cartoon called “Once Upon a Time… Life.” It took place inside a human body, and each type of cell was a character. I remember the immune cells chasing and fighting weird pathogens that were the bad guys. It was a very fun and exciting cartoon, it got me excited about the biology and mechanics of life.

What drives my research? I am just amazed by how the human body works! I'm impressed by the incredible machinery of the human immune system – there are so many parts and so many interactions that lead to the protection provided by our immune cells! And then there is the human microbiome, this portable ecosystem that lives and interacts with our body! It is a privilege to get to study these systems and contribute to understand how they work.

My work on #BlackInImmuno was inspired by the Black-in-X movement, which started and grew in response to incidents of police brutality and murder during the global pandemic. Black researchers were sharing on social media about their experiences facing discrimination in academia, under the thread #BlackInTheIvory. It initiated a reckoning in the scientific community about how Black researchers are experiencing the effects of systemic racism and the need to address inequalities and change the culture.

If the majority of scientists take this problem seriously and decide to dismantle systemic barriers [...], there is a lot that can be achieved in a short amount of time.

JOEL BABDOR, PHD, POSTDOCTORAL SCHOLARUCSF Department of Otolaryngology

What kind of messages did you get about Black people in science/medicine as you were growing up? And what, if anything, do you think anything has changed?

When I was growing up, I didn’t see any examples of Black scientists. It didn't necessarily lead me to think that this was not something that I could do. But it requires more imagination to see yourself in a place where you haven't seen anyone that looks like you. When I started to work in research labs, there were very few Black researchers around. The situation hasn’t changed much.

At UCSF, I’ve co-founded a diversity-equity-inclusion (DEI) initiative called Immunodiverse. In addition to really cool outreach opportunities for researchers, we have developed an Allyship Learning Program: we curate and share resources around a monthly theme (what is systemic racism, what is intersectionality and why does it matter), and organize moderated group discussion meetings for the community to share their thoughts and their learning processes. We hope to start conversations and to create opportunities to learn and take action toward increasing diversity and belonging of researchers minoritized in our institution.

Was there an experience that really affirmed (or reaffirmed) your commitment to your field?

I’ve had some great experiences, first during my thesis with PhD mentor Loredana Saveanu at University of Paris and with my first postdoc with Olivier Hermine at IMAGINE institute. My current postdoc here at UCSF has also been rewarding. My current PI, Matt Spitzer, has given me the space and support to design and develop research projects that I have been thinking about for a decade. I am especially grateful for the leadership opportunity that Matt has created for me, and how he is committed to ensuring that I receive the credit for this leadership. I have learned every critical aspect of being an independent investigator and developed a research program that I want to continue to investigate for the next decades.

I am integrating immune, metabolomic and microbiome data to understand the relationship between these biological compartments. My most advanced project looks at patients with kidney transplants that are under immunosuppression. I am mapping the evolution of their entire immune systems, hoping to understand what leads to rejection of the transplanted organ. My next step is to look at the metabolites circulating in the blood of these patients to see if that gives us information about the bacterial community they have and how it influences their immune system, hoping to find ways to prevent rejection. I have also developed a human study (ImmunoMicrobiome) that looks at the immune system, the microbiome and the metabolome in more than a hundred healthy individuals, looking at how these biological compartments evolve over time. We are using cutting-edge single cell technologies and computational approaches that will help us understand how these systems talk to each other.

What excites you about the next generation of Black people in science and medicine?

I'm excited for the next generation of Black scientists, because of the transformation that the scientific community has initiated. I think we're providing a space that is going to be more welcoming, more diverse in the future.

I would say I've seen a lot of peers growing in their allyship and starting to take action. This is making a big difference. If the majority of scientists take this problem seriously and decide to dismantle systemic barriers that affect underrepresented minorities and Black researchers, there is a lot that can be achieved in a short amount of time.

Gideon St.Helen, PhD, Assistant Professor in the UCSF School of Medicine

Tell us about your work.

My research is a combination of two related fields: toxicology, which deals with poisons, and clinical pharmacology, which deals with drugs. I focus on two broad classes of products, tobacco and cannabis.

When I study cigarettes, which kill almost half a million people in the U.S. and over 7 million people globally every year, my research is purely toxicological. There are wide racial disparities in smoking-related diseases and death in the U.S., with Blacks being disproportionately impacted. The reasons for these disparities aren’t always clear, and some of my research focuses on understanding racial differences in biobehavioral drivers, including genetic/metabolic factors, that potentially lead to differences in exposure to carcinogens and toxicants in tobacco smoke.

When it comes to e-cigarettes and cannabis, I describe my research as clinical pharmacology. I’m trying to understand both the risks as well as potential benefits associated with use of these products. My studies entail giving participants these products under controlled conditions in a hospital research ward to describe the pharmacokinetics (changes in systemic levels) of either nicotine or cannabinoids like THC and acute health effects, such as cardiopulmonary changes, and subjective effects, like craving reduction and satisfaction. The goal is to provide policymakers with robust data to guide regulation of these products and public health policies.

What or who inspires you to work in health/science?

My parents have always been my inspiration. Growing up in St.Lucia, a country with limited resources, we were taught the value of education, that we were to strive for success, to give our best effort, and to contribute to the upliftment of the human family. My young children also inspire my work. I want to show them that doors that seem locked can be opened with the keys that education affords. The past and current struggles of the African diaspora in the West, including entrenched health disparities, continue to motivate my work. The thought of disappointing those who came before, who persisted under much more difficult and oppressive conditions, is unbearable. So, I persist!

The thought of disappointing those who came before, who persisted under much more difficult and oppressive conditions, is unbearable. So, I persist!

GIDEON ST.HELEN, PHD, ASSISTANT PROFESSORUCSF School of Medicine

What kind of messages did you get about Black people in science/health as you were growing up? And what, if anything, do you think anything has changed?

I grew up on an island that is predominantly Black at a time when we had recently gained independence from the United Kingdom. (We celebrated our 42nd year of Independence on February 22.) We are a small nation with two Nobel laureates: Sir Arthur Lewis (economics) and Derek Walcott (literature). We were taught about our strength as a people, about our resilience, and about the beauty of our blackness. We were constantly told that “St.Lucians are intelligent people.” And because “St.Lucians are intelligent people” was reinforced, I fell in love with math and science at an early age. These messages have changed somewhat over the years as St.Lucia becomes more reliant on tourism, shifting the culture towards service and subservience. The allure of independence and Nobel laureates has faded, and “St.Lucians are intelligent people” is said less often.

Was there an experience that really affirmed (or reaffirmed) your commitment to your field?

I have had several experiences that have affirmed my commitment to my field (i.e. toxicology/clinical pharmacology of tobacco and cannabis). One of these is my service in 2017-2018 as a member on a committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), tasked with writing a report on the public health consequences of e-cigarette use. This committee was made up of world experts across disciplines. While I struggled with imposter syndrome throughout, this experience has been a defining moment in my career. Other experiences are ongoing, but equally reaffirming or impactful!

Did you ever have a moment of doubt, in which you thought you might not continue in science/health? And how did you move through that?

Despite the reinforcing childhood message of “St.Lucians are intelligent people,” and phenomenal primary school teachers who built up my self-confidence, I developed a heavy dose of self-doubt while in secondary school. A life-changing event happened when I was 13. After choosing 7 subject areas to focus on during the remaining 2 years of secondary school, I decided that I wanted to drop chemistry after attending the first class. “I think that class is too hard,” I told myself. Mr. Jean, the principal, heard of this “travesty” and called me to his office. There, he told me of my abilities and my potential, and he refused to allow me to drop the chemistry class. It turned out that a knowledge of chemistry was foundational to toxicology and pharmacology.

Academia affords ample opportunities for moments of doubt, including manuscript rejections and not-discussed grant applications. I’m learning to not take these to heart (as they are rarely personal), and to allow for some “grieving time” before using the reviewer comments to strengthen a manuscript or grant proposal for resubmission.

What excites you about the next generation of Black people in science and medicine?

I’m not that old! But the next generation’s innovative use of technology excites me. For example, postdocs in our center are using social media as a tool to aid youth in quitting tobacco. I am also excited by the number of young people who are interested in coding, given the wide applicability of this skill. I’m really excited about the political activism we’ve seen among young people over the past 4 years, including their action on gun violence and protesting racism in the justice system. Finally, I’m excited to see the continued downward trend of smoking among teens.