The Scandinavian nation strives to rehabilitate instead of punish. UCSF’s Amend program is showing that this model can help solve the public health crisis plaguing the American correctional system.

By Ariel Bleicher UCSF Magazine Summer 2021Photo: Gabriela Hasbun

In August 1997, on her first day of clinical rotations as a medical student in New York City, Brie Williams, MD, sat down at the bedside of a young woman. The patient lay on her back, a blanket pulled up to her neck. Staring at the ceiling, she answered Williams’s questions with curt, one-word replies. Finally, Williams asked the woman to sit up so she could examine her.

“No.”

Williams froze. Had she done something wrong? She fidgeted silently, at a loss for words, until at last the woman said, “Why don’t you ask me why I can’t sit up?”

“OK. Why can’t you sit up?”

“Take the blanket off me, and you’ll see.”

Williams lifted the blanket. The woman, who Williams later learned was incarcerated at the nearby Rikers Island jail, was handcuffed to the bed frame.

“In that moment, she taught me that the most important factor in her health care was something so invisible to me that I didn’t even think to ask about it,” Williams says. It was a lesson she brought with her to UC San Francisco, where, as a medical resident and geriatrics fellow, she began studying the often-unseen health effects of imprisonment. By the time she joined the faculty, in 2007, she was one of the nation’s few authorities on the subject. In her expert opinion, the U.S. correctional system – with its overcrowded wards, rapidly aging population, stark racial disparities, and excessive use of force and isolation – has created a public health crisis.

Brie Williams, MD, founded Amend in 2015. In the photo at top, Williams is pictured with San Quentin State Prison medical chief Alison Pachynski, MD ’02 (left), and Amend team members Fernando Murillo, Michele Casadei, and Daryl Norcott, JD. Photo: Gabriela Hasbun

The crisis, as Williams and her colleagues describe it, began in the 1970s, when rising crime rates and ensuing tough-on-crime policies ushered in an era of mass incarceration. American prisons and jails – which in previous decades had focused more on rehabilitation – became harsh, punitive milieus. Guards (now called correctional officers) increasingly responded to behavioral health problems with discipline and separation, including solitary confinement. But instead of becoming safer, many correctional facilities became plagued by violence, sexual assault, and suicide.

This evolution has taken an enormous physical and psychological toll. Today, about 2.3 million people – over 1 in 100 American adults – are behind bars, more than in any other nation. They are disproportionately afflicted with chronic disease, mental illness, and a history of trauma and substance use disorders. The food they’re served is typically unhealthy, leading to obesity and poor nutrition. They are at risk of exposure to toxins like lead and mold and are especially vulnerable to infectious diseases, as COVID-19 has tragically spotlighted. Depression is rampant, as are anxiety, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. Even after someone is released from prison, they’re more likely to die during their first two weeks of freedom than someone in the community of similar age and gender.

And it’s not only incarcerated people who suffer. Around a decade ago, evidence began mounting that the punitive settings were also undermining the health of staff. Officers reported witnessing violence almost daily and worrying constantly about being attacked. They experienced high rates of diabetes, heart disease, mental health problems, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). On average, they die by age 60.

“That got people’s attention,” says Cyrus Ahalt, MPP, a UCSF public health researcher who has worked with Williams since 2010. “We realized these environments are so corrosive that even stepping foot in them as a worker is elevating your risk of stress-related illness and the social outcomes of that, like divorce, addiction, and suicide.”

With Ahalt’s help, Williams, who is now a professor in the Division of Geriatrics, searched for a way to reverse these trends. Her quest led her to found a program called Amend – the name a nod to the Eighth Amendment’s decree against “cruel and unusual punishment.” For the past six years, Amend has worked with legislators and correctional staff in seven states, including California, to turn prison cultures away from retribution and toward health and healing. The program has begun, slowly but surely, to improve the well-being of those who live and work in American prisons.

Williams’s quest started with a simple but radical idea. “I said, ‘Surely there must be a place where public health is the centerpiece of criminal justice,’” she recalls. “We found that place in Norway.”

“In Norway, we have a saying: If you pee your pants on a cold winter day, it will feel very warm, and then it will freeze like hell,” says Tom Eberhardt, who has worked in the Norwegian Correctional Service for 26 years and joined Amend as a consultant last year. The proverb warns against doing something that fixes a problem momentarily but makes it worse in the long run. For Eberhardt, it’s the perfect metaphor for a revenge-driven approach to corrections.

“If a horrible criminal act has been done, it’s only natural to say, ‘Lock them up! Throw away the key! Treat them really bad!’” he says. “That’s revenge – it feels good for a while, but eventually you start to hurt everybody in the prison and in the general society because you are just creating more violence and more revenge.”

Norway, whose prisons are extolled today as some of the most humane in the world, came to this insight the hard way. Until fairly recently, Norwegian correctional facilities were run much like their American counterparts. Officers were quick to punish incarcerated individuals for even minor infractions and typically kept them locked in cells. As one formerly incarcerated Norwegian put it, “they just wanted to catch you or punch you down.” Those who were imprisoned reacted in kind, with verbal and physical assaults, riots, and Hollywood-esque escapes. As many as 70% of Norwegians released from prison reoffended within two years – a recidivism rate now mirrored in the U.S.

That changed in the 1990s, when Norway overhauled its prison system to prioritize rehabilitation and reintegration into society. This shift, which has slashed recidivism to about 20%, followed three basic principles. The first is “normality,” which prescribes that life inside prisons resemble life outside as closely as possible. Nowadays, people incarcerated in Norway often wear their own clothes, cook in communal kitchens, and move about unaccompanied by officers. They might work, take classes, play sports, or shop for groceries. Their cells tend to look like dorm rooms, with throw rugs, curtains, and mini-fridges.

If such amenities sound indulgent, they make sense in the context of the second principle – “progression,” or preparing people in prison for when they get out. “What is done wrong in a lot of prison systems is that they keep people behind bars in high-security environments almost to the day they are released,” Eberhardt says. “Then those people, who are considered too dangerous even to leave a cell, become your neighbors or your friends’ neighbors.” People imprisoned in Norway, by contrast, gradually earn more freedoms by taking on responsibilities or accomplishing goals; as they near the end of their sentences, they can apply to transfer to lower-security facilities or to live or work in the community.

“Everyone in Norway – your taxicab drivers, your waiters – will tell you: People go to court to be punished; they go to prison to become better neighbors,” Williams says. “This is a deeply public-health vision. Every policy, every procedure, every interaction in a prison is scrutinized for its capacity to help people and the community heal.”

Everyone in Norway will tell you: People go to court to be punished; they go to prison to become better neighbors.”

BRIE WILLIAMS, MD

It is the third principle of Norwegian corrections that makes this healing possible. Known as “dynamic security,” it focuses on the role of prison workers. Norway’s correctional officers routinely socialize with residents, joining them for meals and card games and talking through problems. Officers are trained to use force when absolutely necessary but also study law, ethics, human rights, and the science of behavior change. They learn that building positive relationships with incarcerated people helps them get their lives on track and reduces the risk of violence. Even in maximum-security prisons – where most people are in custody for violent crimes like murder or rape – assaults against officers are rare, Eberhardt says.

That may sound counterintuitive if you’ve been taught to think of security in terms of barriers, weapons, oppressive rules, and threats of added punishment. But a Norwegian officer will explain that getting to know incarcerated people on a personal level better alerts you to potential conflict and earns you their respect. “A lot of my colleagues, they will say, ‘If you meet an ex-inmate in a pub, there’s a much bigger chance he will buy you a beer than knock you down,’” Eberhardt says. “It’s true. Whenever I’ve met formerly incarcerated people on the outside, they are often thanking me. It’s always a very rewarding experience.”

When Williams first visited Norwegian prisons, in 2014, she was surprised to hear so many officers say they loved their jobs. They weren’t overly stressed and hypervigilant. They didn’t perpetually fear for their safety. They didn’t think about killing themselves or take out their frustrations on their families. Williams knew she’d found the model system she’d been searching for – the basis for Amend. It gave prison residents a chance at a healthy, meaningful life and made the lives of staff healthier and more meaningful, too.

If Norway could pull that off, she thought, why not the U.S.?

Since its inception in 2015, Amend has arranged for U.S. policymakers and correctional leaders to travel to Norway to see for themselves how its prisons operate. Williams calls these “hearts and minds tours.”

Norwegian officers traveled to North Dakota in February 2020 to provide hands-on training to prison correctional staff as part of Amend’s culture-change program. Photo: Brie Williams

Beforehand, the travelers are almost unanimously skeptical. Norway’s approach to corrections would never work in the U.S., they insist; the two countries simply are too different – different values, different politics, different demographics. “We hear ‘Norway’s so socialist’ or ‘Norway’s all white,’ which is actually not true,” says Ahalt, who is now Amend’s chief program officer. About two-fifths of those incarcerated in Norway are from Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, making Norway’s prisons more racially and ethnically diverse than is often assumed.

But once Amend participants visit Norwegian prisons, Ahalt says, “the skepticism and resistance evaporate.” The visitors realize, from observing and talking with prison workers and residents, that the key to their relative well-being is not some quirk of Norwegian society or even the comforts in some prisons. “The message is ‘You can treat incarcerated people with humanity; you can be invested in their success; you can play a positive role in ending the cycle of incarceration and violence,’” Ahalt says. “That is universal.”

You can treat incarcerated people with humanity. That is universal.”

CYRUS AHALT, MPP

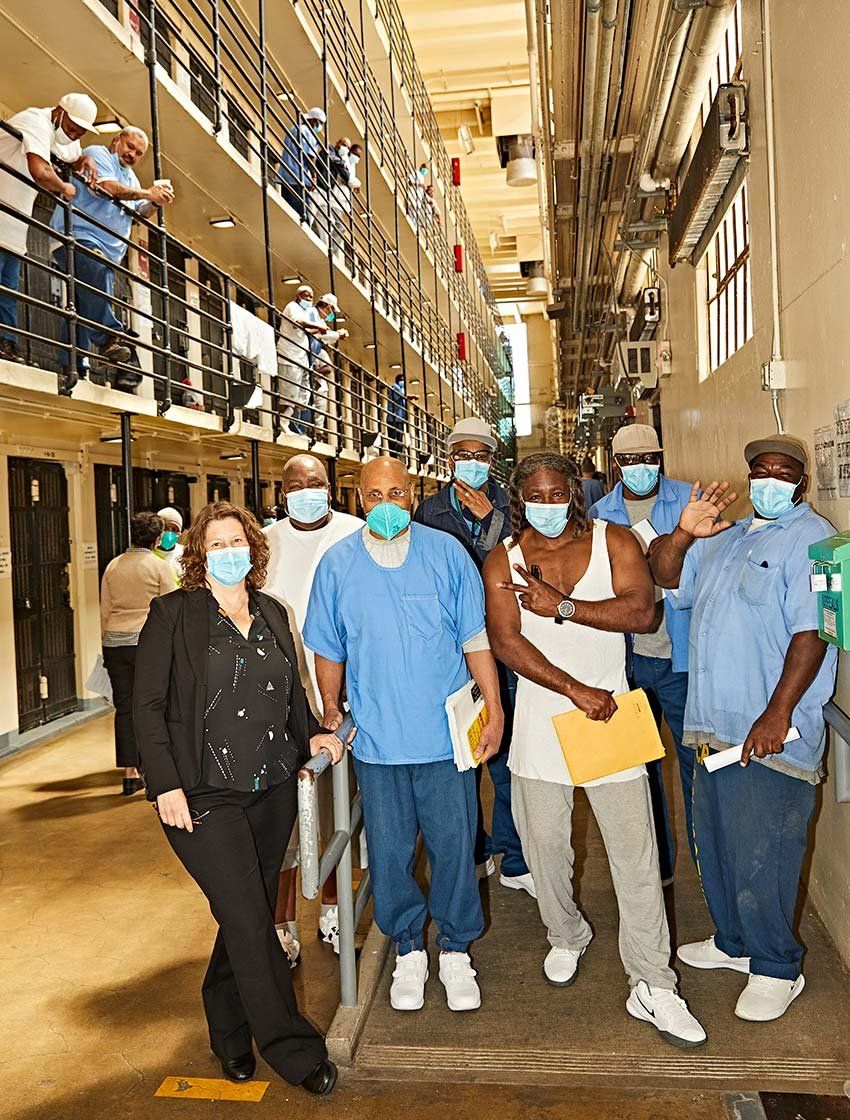

Amend partners with incarcerated people, community leaders, and advocates to reduce the debilitating health effects of U.S. prisons. “Mass incarceration is a public health crisis,” says Amend director Brie Williams, MD (left). Photo: Gabriela Hasbun

Still, Norway’s system has some advantages. For one, the country does not share the U.S.’s legacy of systemic racism, born of chattel slavery, which has led to disproportionate imprisonment of non-white men. Norwegians also are far less likely than Americans to be sent to prison for minor criminal offenses, and the longest sentence they face is 30 years – compared to U.S. sentences of over 10,000 years. As a result, Norway’s prisons are far less crowded, with as few as one staff member for each incarcerated person.

It would thus be hard to precisely replicate Norway’s model in the U.S. But, says Williams, that’s not Amend’s goal. “We’re not trying to create mini-Norways,” she says. Rather, with Amend’s guidance, Norway gives American prisons inspiration for making their own reforms.

These reforms are happening as much from the bottom up as from the top down. In 2018, Amend launched a culture-change program, which offers job-shadowing and hands-on training with Norwegian officers for American correctional staff. To date, over 400 officers in California, North Dakota, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington have enrolled.

David Jantz, now a captain at Oregon’s Snake River Correctional Institution, was one of the first. For most of his career, he found corrections work pretty miserable. “Eight hours a day of doing tier checks and a couple shakedowns – there’s not a lot of job satisfaction in that,” he says. Just putting on his uniform made his heartbeat rise. He believed his sole duty was keeping incarcerated people in line. “If you would’ve asked me back then what was wrong with our population, I would have said, ‘They think they’re human, and we need to dial them back in.’”

Jantz remembers the moment his mind began to change. It was the first day of his Amend training, and the class was role-playing on-the-job scenarios. Jantz was playing an officer trying to get an uncooperative person out of a cell. “I announce who I am, and I pound on the door,” he recalls. Two more officers stand behind him, ready to back him up in case things get rough. Jantz tells the person in the cell, “Hey, I need you to move your leg or something, so I know you’re OK.” Silence. Jantz pounds harder. “Then I start kicking the door,” he says, and the Norwegian instructor “looks at me horrified.”

“Why would you do that?” he asks Jantz.

“That’s the way I was trained,” Jantz replies.

Then they switch roles, and Jantz gets in the cell. From inside, he sees three officers peering in at him intimidatingly. “When they start yelling and kicking the door, I can literally feel my irritation starting to rise – like, at any split second, the scenario could become confrontational.” At this point the instructor steps in and takes a different tack. He tells the back-up officers to stand off to the side, still close but out of Jantz’s view. He speaks calmly, asks if Jantz is OK, says he just wants to talk. Jantz feels his body relax, and he opens the door – no confrontation necessary.

“That’s when the value of the training started to sink in,” Jantz recalls, “because it simply made sense: ‘Be human.’ It’s not really that complex. Me and the other officers, we just didn’t know it. Prior to Amend, we thought if you had an opportunity to take care of business and go home safe, that was a pretty good day. Boy, how wrong were we?”

Since 2019, Amend has worked closely with correctional officers in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to improve the health and well-being of people who live and work in the state’s prisons. Photo: Gabriela Hasbun

Amend has inspired prisons to rethink dehumanizing practices like the use of force and solitary confinement, with measurable impact. North Dakota’s department of corrections, for instance, has decreased its use of solitary confinement by 80%. And Jantz’s unit at Snake River has helped six men get out of long-term isolation, including one man who’d been confined alone for over a decade.

“I was pulled out [of my cell] one day and brought into a conference room where 10 [correctional] staff members told me they all had a vested interest in my success,” the man later wrote to Amend’s staff. Before that, he confessed, he saw himself as fundamentally broken. But the Amend-trained officers gave him a new lease on life. “These people treated me like anyone in society would treat me, rather than [as] a burden,” he wrote. “This ultimately has made me feel like I’m equally worthy of returning back into society, and for this I am truly grateful.”

“One of the biggest skills you get from Amend is just listening,” says Daniel Moyer, a sergeant at Salinas Valley State Prison, who started Amend training last fall. (During the pandemic, Amend shifted its culture-change program to a virtual platform.) “A lot of guys in custody know you’re not going to be able to solve all their problems, but as long as they feel like you care, that usually does a pretty good job of de-escalating the situation.”

Officers can proudly tell their kids about somebody’s life they helped change.”

BRIE WILLIAMS, MD

The benefits extend to prison staff. Officers at one prison who enrolled in Amend’s culture-change program were 60% less likely to have been assaulted six months later. They also reported fewer PTSD symptoms, less concern about their own drinking and overall health, and better relationships with family and friends. “We have officers who say they can look at themselves in the mirror for the first time in 10 years because they can finally feel good about what they do,” Williams says. “They can sit down at the dinner table and proudly tell their kids about somebody’s life they helped change.”

Considering the vastness of the U.S. correctional system, it might be tempting to dismiss such progress as a drop in the bucket. There is, to be sure, much more that needs to be done to mitigate the harm that incarceration inflicts on American communities, and Amend is only part of the solution. But a true revolutionary will remind you that the seeds of change often start small and grow. “When you give people a vision and skills for a different approach, they start to demand more from themselves and from their profession,” Williams says. “It becomes almost like a social movement – you can’t stop it.”