In what is believed to be the first large-scale study to quantify the development of breast cancer according to the degree of glandular tissue (which appears dense on mammogram, versus fat, which appears non-dense), researchers headed by UC San Francisco evaluated risk factors in more than 200,000 women. The participants were aged between 40 and 74 and were enrolled in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, a research initiative designed to assess the delivery and quality of breast cancer screening. Approximately 18,000 of the women had varying stages of breast cancer, while around 184,000 did not.

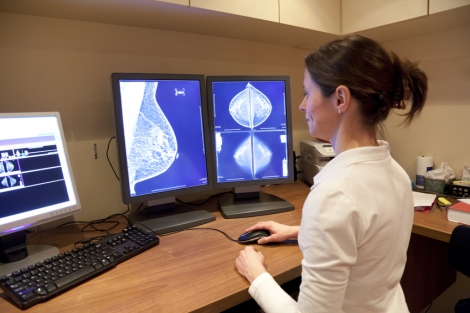

Breast density, or degree of glandular tissue, was reported for each woman according to the four categories established by the American College of Radiology’s Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS). These comprise: category A, breasts composed almost entirely of fat; category B, those with scattered dense tissue but mostly fat; category C, those with moderately dense tissue and category D, those in which dense tissue makes up at least 75 percent of the breast.

The findings were published in the journal JAMA Oncology on Feb. 2.

Higher BMI Linked to Lower Density

“Typically women with a high BMI have lower breast density, though age is a strong determinant of breast density as well,” said first author Natalie Engmann, a PhD candidate in the UCSF Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics. “Dense breasts are more common in younger women and most women experience a sharp decline during menopause that continues in the post-menopausal period. However, post-menopausal estrogen and progestin therapy can reverse the decline of breast density with age.”

The researchers compared the “population attributable risk” of breast cancer risk factors, which assesses the impact of each risk factor on the development of disease in an entire population. They calculated the effect of each risk factor, using 18,437 women with breast cancer, compared to 184,309 women of the same age who did not have the disease.

They found that breast density was the most prevalent risk factor and that 39.3 percent of breast cancers in pre-menopausal women and 26.2 percent in post-menopausal women had the potential to have been prevented if all women with higher breast density, BI-RADS categories C and D, had been shifted to lower-density BI-RADS category B.

“Treatment with tamoxifen, an estrogen hormone blocker, is the only intervention currently known that substantially reduces breast density and thus reduces breast cancer risk,” said Engmann. “However, tamoxifen can have serious side effects and is generally only recommended for women at high risk of breast cancer, with guidance from their physician. Our study highlights the need for new interventions to reduce breast density for women at average risk.”

The elevated risk of breast cancer in women with dense breasts is attributed to the high cellular content of dense tissue and interaction between cells that line the mammary ducts and surrounding tissue. Additionally, both tissue and cancer appear white on mammograms, making it harder for radiologists to flag malignancy in dense tissue than in fat, which appears dark.

While the link between dense breasts and breast cancer suggests that carrying extra pounds may have a protective effect against the disease, since overweight and obese women are more likely to have fatty breasts, the study reinforced previous research that has established a link between high body mass index and heightened breast cancer risk in post-menopausal women.

The researchers found that 22.8 percent of breast cancers in this group could have been averted if obese and overweight women attained a body mass index of less than 25, the equivalent of 155 lbs for a woman of 5 feet 6 inches.

Family History Presents Small Risk

By contrast, the study found that factors commonly associated with breast cancer risk accounted for less than 10 percent of cases in the population. A history of benign breast biopsy, for example, was associated with 6.9 percent of breast cancer in pre-menopausal women and 8.6 percent among post-menopausal women. A first-degree family history of breast cancer was linked to 8.7 percent of cases among pre-menopausal women and 8.2 percent of cases in post-menopausal women. And deferring childbirth until after age 30 was associated with an 8.7 percent risk in pre-menopausal women and 5.2 percent among those who were post-menopausal.

“The most significant finding in this study is the impact of breast density on development of breast cancer in the population,” said senior author Karla Kerlikowske, MD, professor of medicine and of epidemiology and biostatistics in the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. “We found that if breast density could be reduced by a single BI-RADS category, 13.4 percent of breast cancers in both pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women could be averted. Finding interventions that can reduce breast density, such as breastfeeding and/or increased number of children and birth of children before age 30, could contribute to preventing more cases than reducing any other risk factor in the study.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 230,815 women were diagnosed with breast cancer and 40,860 died from it in 2013. In the same year 2,109 men were diagnosed with breast cancer and 464 died from it.

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute-funded Program Project grant P01 CA154292.

Study co-authors are Marzieh Golmakani of the University of California, Davis; Diana Miglioretti PhD, of the University of California, Davis, and the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle; and Brian Sprague, PhD, of the University of Vermont in Burlington.

This article was written by Suzanne Leigh and originally published by UCSF.